L’empire mondial anglo-nazi qui a failli émerger après Munich !

Article rédigé le 4 mai 2025 par Kit Klarenberg sur son compte Substack

Toutes mes enquêtes sont en lecture libre, grâce à la générosité de mes lecteurs. Le journalisme indépendant nécessite néanmoins des investissements, donc si vous appréciez cet article ou d’autres, veuillez envisager de le partager, ou même de devenir un abonné payant. Votre soutien est toujours reçu avec gratitude et ne sera jamais oublié. Pour m’acheter un café ou deux, veuillez cliquer sur ce lien.

À l’approche du Jour de la Victoire en Europe, les responsables, les experts et les journalistes occidentaux cherchent largement à exploiter le 80e anniversaire de la défaite du nazisme à des fins politiques. Les dirigeants européens ont menacé de conséquences négatives les participants à la grande parade de la victoire russe du 9 mai. Pendant ce temps, d’innombrables sources établissent des comparaisons historiques entre l’apaisement de l’Allemagne nazie tout au long des années 1930 et les efforts continus de l’administration Trump pour conclure un accord avec Moscou afin de mettre fin au conflit par procuration en Ukraine.

Comme l’a écrit The Atlantic en mars, « Trump offre à Poutine un autre Munich » – une référence à l’accord de Munich de septembre 1938, en vertu duquel les puissances occidentales, dirigées par la Grande-Bretagne, ont accordé une vaste partie de la Tchécoslovaquie à l’Allemagne nazie. Les récits dominants de l’apaisement affirment que cela représentait l’apothéose de la politique - son dernier acte, dont on croyait qu’il assouvierait de façon permanente les ambitions expansionnistes d’Adolf Hitler, mais rendait en fait la Seconde Guerre mondiale inévitable.

Appeasement is universally accepted today in the West as a well-intentioned but ultimately catastrophically failed and misguided attempt to avoid another global conflict with Germany, for peace’s sake. According to this reading, European governments made certain concessions to Hitler, while turning a blind eye to egregious breaches of the post-World War I Versailles Treaty, such as the Luftwaffe’s creation in February 1935, and Nazi Germany’s military occupation of the Rhineland in May the next year.

In reality though, from Britain’s perspective, the Munich Agreement was intended to be just the start of a wider process that would culminate in “world political partnership” between London and Berlin. Two months prior, the Federation of British Industries (FBI), known today as the Confederation of British Industry, made contact with its Nazi counterpart, Reichsgruppe Industrie (RI). The pair eagerly agreed their respective governments should enter into formal negotiations on Anglo-German economic integration.

Representatives of these organisations met face-to-face in London on November 9th that year. The summit went swimmingly, and a formal conference in Düsseldorf was scheduled for next March. Coincidentally, later that evening in Berlin, Kristallnacht erupted, with Nazi paramilitaries burning and destroying synagogues and Jewish businesses across Germany. The most infamous pogrom in history was no deterrent to continued discussions and meetings between FBI and RI representatives. A month later, they inked a formal agreement on the creation of an international Anglo-Nazi coal cartel.

British officials fully endorsed this burgeoning relationship, believing it would provide a crucial foundation for future alliance with Nazi Germany in other fields. Moreover, it was hoped Berlin’s industrial and technological prowess would reinvigorate Britain’s economy at home and throughout the Empire, which was ever-increasingly lagging behind the ascendant US. In February 1939, representatives of British government and industry made a pilgrimage to Berlin to feast with high-ranking Nazi officials, in advance of the next month’s joint conference.

As FBI representatives prepared to depart for Düsseldorf in March, British cabinet chief Walter Runciman - a fervent advocate of appeasement, and chief architect of Czechoslovakia’s carve up - informed them, “gentlemen, the peace of Europe is in your hands.” In a sick twist, they arrived on March 14th, while Czechoslovakian president Emil Hácha was in Berlin meeting with Hitler. Offered the choice of freely allowing Nazi troops entry into his country, or the Luftwaffe reducing Prague to rubble before all-out invasion, he suffered a heart attack.

After revival, Hácha chose the former option. The Düsseldorf conference commenced the next morning, as Nazi tanks stormed unhindered into rump Czechoslovakia. Against this monstrous backdrop, a 12-point declaration was ironed out by the FBI and RI. It envisaged “a world economic partnership between the business communities” of Berlin and London. That August, FBI representatives secretly met with Herman Göring to anoint the agreement. In the meantime, the British government had via back channels made a formal offer of wide-ranging “cooperation” with Nazi Germany.

‘Political Partnership’

In April 1938, journeyman diplomat Herbert von Dirksen was appointed Nazi Germany’s ambassador to London. A committed National Socialist and rabid antisemite, he also harboured a particularly visceral loathing of Poles, believing them to be subhuman, eagerly supporting Poland’s total erasure. Despite this, due to his English language fluency and aristocratic manners, he charmed British officials and citizens alike, and was widely perceived locally as Nazi Germany’s respectable face.

Even more vitally though, Dirksen - in common with many powerful elements of the British establishment - was convinced that not only could war be avoided, but London and Berlin would instead forge a global economic, military, and political alliance. His 18 months in Britain before the outbreak of World War II were spent working tirelessly to achieve these goals, by establishing and maintaining communication lines between officials and decisionmakers in the two countries, while attempting to broker deals.

Dirksen published an official memoir in 1950, detailing his lengthy diplomatic career. However, far more revealing insights into the period immediately preceding World War II, and behind-the-scenes efforts to achieve enduring detente between Britain and Nazi Germany, are contained in the virtually unknown Dirksen Papers, a two-volume record released by the Soviet Union’s Foreign Languages Publishing House without his consent. They contain private communications sent to and from Dirksen, diary entries, and memos he wrote for himself, never intended for public consumption.

Documents And Materials Relating To The Eve Of The Second World War Ii

21.6MB ∙ PDF file

The contents were sourced from a vast trove of documents found by the Red Army after it seized Gröditzberg, a castle owned by Dirksen where he spent most of World War II. Mainstream historians have markedly made no use of the Dirksen Papers. Whether this is due to their bombshell disclosures posing a variety of dire threats to established Western narratives of World War II, and revealing much the British government wishes to remain forever secret, is a matter of speculation.

Immediately after World War II began, Dirksen “keenly” felt an “obligation” to author a detailed post-mortem on the failure of Britain’s peace overtures to Nazi Germany, and his own. He was particularly compelled to write it as “all important documents” in Berlin’s London embassy had been burned following Britain’s formal declaration of war on September 3rd 1939. Reflecting on his experiences, Dirksen spoke of “the tragic and paramount thing about the rise of the new Anglo-German war”:

“Germany demanded an equal place with Britain as a world power…Britain was in principle prepared to concede. But, whereas Germany demanded immediate, complete and unequivocal satisfaction of her demands, Britain - although she was ready to renounce her Eastern commitments, and…allow Germany a predominant position in East and Southeast Europe, and to discuss genuine world political partnership with Germany - wanted this to be done only by way of negotiation and a gradual revision of British policy.”

‘German Reply’

From London’s perspective, Dirksen lamented, this radical change in the global order “could be effected in a period of months, but not of days or weeks.” Another stumbling block was the British and French making a “guarantee” to defend Poland in the event she was attacked by Nazi Germany, in March 1939. This bellicose stance - along with belligerent speeches from Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain - was at total odds with simultaneous conciliatory approaches such as Düsseldorf, and the private stances and utterances of British officials to their Nazi counterparts.

In any event, it appears London instantly regretted its pledge to defend Poland. Dirksen records in his post-mortem how subsequently, senior British officials told him they sought “an Anglo-German entente” that would “render Britain’s guarantee policy nugatory” and “enable Britain to extricate her from her predicament in regard to Poland,” so Warsaw would “be left to face Germany alone”.

In mid-July 1939, Horace Wilson - an extremely powerful civil servant and Chamberlain’s right hand man - approached Göring’s chief aide Helmuth Wohlthat during a visit to London. Wilson “outlined a program for a comprehensive adjustment of Anglo-German relations” to him, which amounted to a radical overhaul of the two countries’ “political, military and economic arrangements.” This included “a non-aggression pact”, explicitly concerned with shredding Britain’s “guarantee” to Warsaw. Dirksen explained:

“The underlying purpose of this treaty was to make it possible for the British gradually to disembarrass themselves of their commitments toward Poland, on the ground that they had…secured Germany’s renunciation of methods of aggression.”

Elsewhere, “comprehensive” proposals for economic cooperation were outlined, with the promise of “negotiations…to be undertaken on colonial questions, supplies of raw material for Germany, delimitation of industrial markets, international debt problems, and the application of the most favoured nation clause.” In addition, a realignment of “the spheres of interest of the Great Powers” would be up for discussion, opening the door for further Nazi territorial expansion. Dirksen makes clear these grand plans were fully endorsed at the British government’s highest levels:

“The importance of Wilson’s proposals was demonstrated by the fact that Wilson invited Wohlthat to have them confirmed by Chamberlain personally.”

During his stay in London, Wohlthat also had extensive discussions with Overseas Trade Secretary Robert Hudson, who told him “three big regions offered the two nations an immense field for economic activity.” This included the existing British Empire, China and Russia. “Here agreement was possible; as also in other regions,” including the Balkans, where “England had no economic ambitions.” In other words, resource-rich Yugoslavia would be Nazi Germany’s for the taking, under the terms of “world political partnership” with Britain.

Dirksen outlined the contents of Wohlthat’s talks with Hudson and Wilson in a “strictly secret” internal memo, excitedly noting “England alone could not adequately take care of her vast Empire, and it would be quite possible for Germany to be given a rather comprehensive share.” A telegram dispatched to Dirksen from the German Foreign Office on July 31st 1939 recorded Wohlthat had informed Göring of Britain’s secret proposals, who in turn notified Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Dirksen noted elsewhere Wohlthat specifically asked the British how such negotiations “might be put on a tangible footing.” Wilson informed him “the decisive thing” was for Hitler to “[make] his willingness known” by officially authorising a senior Nazi official to discuss the “program”. Wilson “furthermore strongly stressed the great value the British government laid upon a German reply” to these offers, and how London “considered that slipping into war was the only alternative.”

‘Authoritarian Regimes’

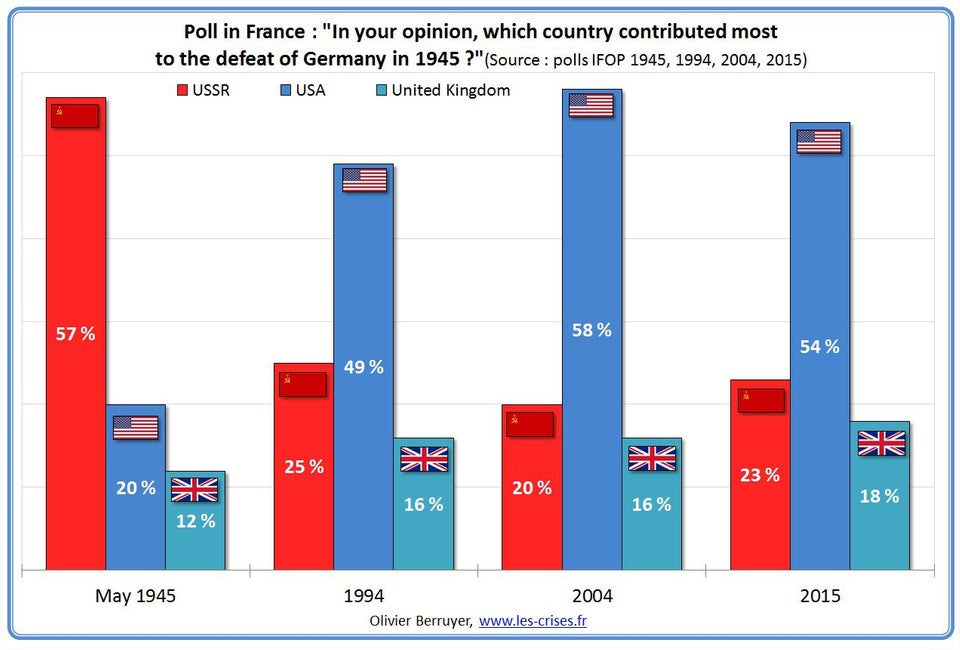

No “reply” apparently ever came. On September 1st 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Britain declared war on Germany two days later, and the rest is history - albeit history that is subject to determined obfuscation, constant rewriting, and deliberate distortion. Polls of European citizens conducted in the immediate aftermath of World War II showed there was little public doubt that the Red Army was primarily responsible for Nazi Germany’s destruction, while Britain and the US were perceived as playing mere walk-on roles.

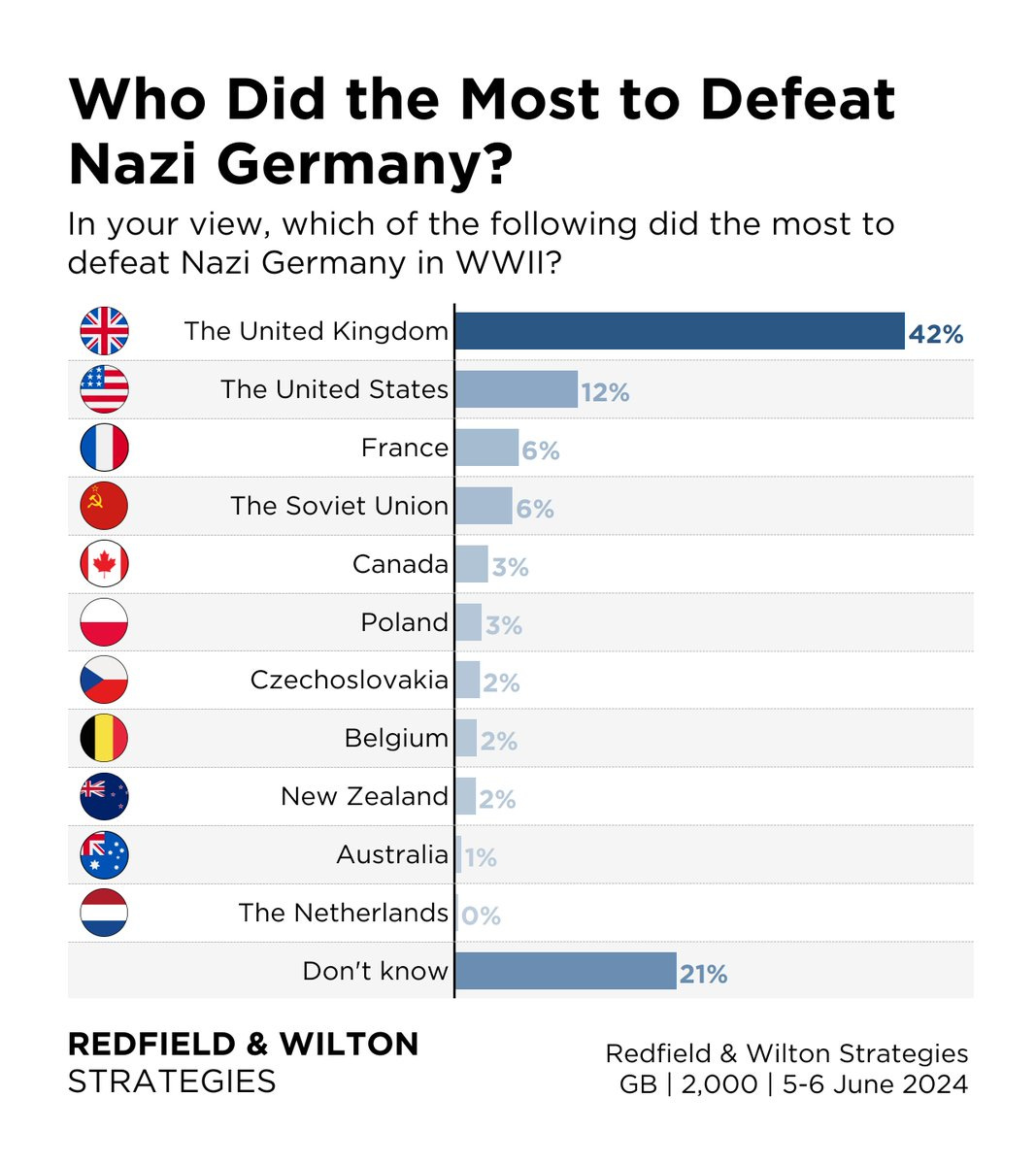

For example, in 1945, 57% of French citizens believed Moscow “contributed most to the defeat of Germany in 1945” - just 20% named the US, and 12% Britain. By 2015, less than a quarter of French respondents recognised the Soviet role, with 54% believing the US to be Nazism’s ultimate vanquisher. Meanwhile, a survey on the 80th anniversary of D-Day in June 2024 found 42% of Britons believed their own country had done more to crush Hitler than all other allies combined.

The same poll identified a staggering level of ignorance among British citizens of all ages about World War II more generally, with only two thirds even able to place D-Day as having occurred during that conflict. The pollsters didn’t gauge public knowledge of Britain’s long-running, concerted attempts to forge a global Empire with Nazi Germany in the War’s leadup, although betting is high that the figure would be approximately zero.

Entre-temps, en 2009, le Parlement européen a institué une commémoration annuelle le 23 août, pour « marquer la Journée européenne du souvenir des victimes de tous les régimes totalitaires et autoritaires ». Ce n’est qu’une des nombreuses initiatives modernes visant à confondre de manière perverse le communisme et le nazisme, tout en transformant les collaborateurs de la Wehrmacht et de la SS, les auteurs de l’Holocauste et les fascistes dans les pays libérés par l’Armée rouge en victimes, et en rejetant la responsabilité de la Seconde Guerre mondiale sur la Russie, en vertu du pacte Molotov-Ribbentrop.

Ce que les responsables de Londres ont proposé à Hitler en 1939 a éclipsé de loin les termes de cet accord controversé, mais il n’y aura bien sûr aucune considération à ce sujet lorsque le Jour de la Victoire en Europe sera célébré dans les capitales occidentales en 2025. En Grande-Bretagne, le gouvernement a « encouragé » le public à organiser des fêtes de rue et à assister à une marche de plus de 1 300 soldats en uniforme de Parliament Square à Buckingham Palace. C’est une ironie amère que le cortège commence et se termine aux endroits mêmes où, il y a huit décennies, le soutien à l’Allemagne nazie était le plus fort à Londres.

Abonnez-vous à Global Delinquents

Par Kit Klarenberg · Des centaines d’abonnés payants

Le rôle des services de renseignement dans la formation de la politique et des perceptions.

S’inscrire

En m’abonna